-

Introduction

Ever since Darwin and the discovery of DNA it has been clear that humans are a species that has evolved from a great ape ancestor, along with chimpanzees and bonobos. Yet, it is manifestly evident that human evolution has been dramatically different from that of all other apes. The human ability to work in large groups and develop technologies is simply not present in other mammalian species. Many mechanisms have been proposed to account for the extraordinary path of human evolution, including cultural group selection, kin selection and reciprocity, and genetic group selection. These and others have been extensively reviewed in a paper by (Richerson et al. 2016). None of these represent an all-embracing theory of human development. Although all recognised the importance of group interaction, none of the analyses specifically focussed on the role of communities in the evolutionary process. This paper proposes that it is community interaction that has been largely responsible for the extraordinary evolution of human society over the last 10,000 years.

-

Culture and memes

The word culture has many meanings and its use by many academic disciplines can cause confusion. In the words of anthropologist E.B. Tylor, it is ‘that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.’(Tylor 1974). It is not always clear whether this includes material culture, such as technology and architecture, or the organisational structures of a society, such as how leaders relate to followers and the interaction of the various subcommunities.

The picture has been further muddied by the concept of cultural traits. Michael O’Brien and others (O’Brien et al. 2010) define cultural traits as ‘units of transmission that permit diffusion and create traditions – patterned ways of doing things that exist in identifiable form over extended periods of time’. This adds innate behavioural tendencies to the definition of culture. Peter Turchin (Peter Turchin 2016) describes cultural traits as ‘quantitative( smoothly-varying) characteristics that cannot easily be represented as discrete alternatives; for example the inclination to trust strangers’. Altruism is usually considered a cultural trait.

An alternative approach was taken by Richard Dawkins, who introduced the word ‘meme’ to describe an idea that could be copied from one animal brain to another, allowing both of them to demonstrate the same skills and behaviours. Since its introduction, the use of the term meme in the study of cultural evolution has stalled. Whilst it is clear that memetic evolution exhibits phylogenetic behaviour (Mesoudi, Whiten, and Laland 2004), no clear use of the term or mechanism for its propagation has been established.

Never-the-less I am going to persist with memes, but define them much broader than Dawkins, as: skills, behaviours and concepts held in common by a number of individuals. By concepts I mean non-material ideas such as colour and sound and shared abstractions like emotions and beliefs. My definition of behaviours includes the established relational norms that determine how power and control is exercised. The definition excludes innate behavioural traits which I view as genetically determined.

-

Communities

Another concept introduced in the Selfish Gene(Dawkins 1976) by Dawkins was that of a replicator. Dawkins said that memes like genes are replicators; they can be copied reasonably faithfully; they can mutate and they can confer an evolutionary advantage to a ‘vehicle’. The ‘vehicles’ for genes are life-forms, which are all involved in a Darwinian struggle of survival of the fittest in order to preserve their genes. The question is ‘what is the vehicle of a meme?’ Daniel Dennett conceived the vehicle of memes to be a human brain in which memes behaved like viruses competing for the attention of an individual.(Dennett 2017). To me this misses the point, the essence of memes is that they are shared between animals. I view the vehicle of memes as a community of animals.

The term community is commonly used in at least three disciplines archaeology, anthropology and sociology. It can have connotations of place as in ‘rural community’, or those sharing common skills as in the ‘scientific community’, or those sharing the same culture as in the ‘Jewish community’. From an evolutionary perspective it is necessary to firm up the definition. This paper considers a community as a group of animals which:

- Shares a common set of memes

- Has a recognisable continuity as an operating unit, able to survive the addition of new individuals as well as accommodate limited membership loss.

- Demonstrates a phylogenetic propensity to propagate a set of memes.

I am going to argue that just as genetic evolution is a result of a struggle for survival by life-forms, memetic evolution is a result of communities acting in their own self-interest. Successful communities will thrive and propagate their memes. The unique memes of failed communities will die out.

The idea that evolution occurs when behavioural norms practiced within successful groups lead to the displacement, absorption or even extinction of other groups is the same as that proposed by those who favour cultural group selection theory such as (Boyd and Richerson 2010). However, much of the emphasis of cultural group selection theory has focussed on the development of prosociality amongst humans and the genetic development of cultural traits. Henrich (Henrich 2004) on the other hand prefers to emphasise the co-evolution of genes and culture as separate interacting processes. This view is supported by Mark Pagel, in his book Wired for Culture (Pagel 2012) in which he develops the idea of cultural evolution, which excludes cultural traits, in explaining the development of human co-operation and community interaction.

Just as genetical evolution brings together the sets of genes that produce a successful biological species or vehicle for a particular environment, cultural evolution brings together the sets of ideas, technologies, dispositions, beliefs and skills that over the millennia have produced successful societies, good at competing with others like them, and well adapted culturally to their particular locale.

The use of the term meme eliminates the confusion between Heinrich’s cultural transmission and the more all-embracing concept of culture of those that support cultural group selection. This paper supports Henrich’s view that human evolution is a product of the co-evolution of genes and culture(memes). It goes further however to aver that it is memetic evolution and the resultant interaction between human communities that has been largely responsible for the dramatic changes in human development that have occurred in the last 10,000 years.

-

Unique Characteristics of human communities

Human communities are not the only animal species to transmit memes from generation to generation. There are many mammal communities, such as prides of lions or herds of elephants, who train successive generations to hunt and forage for food. Chimpanzees have famously used tools such as sticks or straws to capture and eat insects and grubs. Such communities have also cultivated modes of behaviour to maintain community cohesion. However, human communities have taken the ability to transmit memes to a completely different level. I am going to suggest that there are two characteristics that set human communities apart from other mammals, pro-social behaviour and the power of speech.

4.1 Pro-social behaviour

The fundamental basis for community cohesion is the division of the human world between out-groups and in-groups or ‘them’ and ‘us’. Since Henri Tajfel introduced the social identity theory of group behaviour(Tajfel 1974) many researchers have shown that merely identifying someone as one of ‘us’ changes our behaviour towards them. Within communities, antagonistic behaviour is supressed, collaborative behaviour dominates and the level of human interaction necessary for meme propagation exists.

Chimpanzees exhibit many aspects of collaborative behaviour such as cultivating allies through grooming, cooperating in foraging expeditions and predation of monkeys. The fact they also identify themselves as a kin group is demonstrated in the violent conflict that occurs between chimpanzee bands. (Goodall 1988). At some stage during hominid evolution our ancestors acquired the additional instincts and feelings, conceived of as cultural traits, which allowed humans to cooperate on a greater scale. Michael Tomasello (Tomasello et al. 2012) makes the case that these may have emerged as humans became scavengers. Peter Turchin (Peter Turchin 2016) speculates that these were necessary to maintain band cohesion once humans developed the ability to throw lethal projectiles. It would have become much more difficult for an alpha male to win his battles once weapons had been invented. Only bands in which males cooperated in a more egalitarian fashion would have been able to survive.

4.2 The power of speech

The power of speech gives humans an enhanced ability to transmit skills, knowledge and instructions. But it is the facility to share abstract concepts that makes humans unique. According to Lisa Feldman Barrett’s theory of constructed emotion (Barrett 2017), humans perceive the world through concepts held in their brains. Without the brain constructing a conceptual model of the world around it from sensory inputs, humans would experience a ‘world of fluctuating noise’. By associating a word with a concept, two humans could for the first time share the same perception. This includes physical concepts like trees, faces and houses, and action concepts like hitting, running and dancing. Most importantly, for the purpose of this analysis, it allowed abstract concepts like colour, emotions and beliefs to be communicated and understood for the first time.

It is my contention that the power of speech allowed cooperative cultural traits to be identified, understood and exploited to support community cohesion. We know that judging a person as one of ‘them’ or ‘us’ can invoke feelings of antagonism or kinship. In the same way humans can also judge behaviour as good or bad and respond emotionally. The positive emotions of compassion, pride, gratitude, respect and comradeship could be shared and encouraged. The negative emotions of guilt, shame, embarrassment, anger and disgust could be displayed to bring miscreants into line. Community norms are thus reinforced by appeals to emotional feelings that are genetically enabled.

This observation is consistent with a study of 15 diverse populations by Henrich et al (Henrich et al. 2010) in which he concluded that human prosociality is a product of genetically engendered cultural traits and the established norms of the community.

-

Characteristics of memetic evolution

When Dawkins first developed the idea of a meme, I think he envisioned a small discrete unit analogous to a gene. It has since proved infeasible to determine the unit of a meme or visualise it by brain scanning. It therefore will probably be impossible to discover the equivalent of the ‘DNA’ of a meme. The same intricate analysis that has developed for genetic evolution will therefore not be practical for memetic evolution. However just as Darwin was able to develop his theories of evolution through examining life-forms and their particular niche role in the natural world, it is possible to analyse the path of memetic evolution through the development of different types of communities and their interaction with society as a whole.

I am going to argue that communities are vehicles and memes are replicators in an evolutionary process in which communities interact with each other, other life-forms and the environment. To be an evolutionary process there are at least six characteristics that memetic evolution has to demonstrate: I believe these to be:

- Replicators can be copied reasonably faithfully, occasionally mutate and confer an evolutionary advantage to a vehicle.

- Vehicles survive sufficiently long to maintain and develop replicators.

- There is a ‘vehicle world’ in which vehicles play specific roles.

- There is a competitive process in which some vehicles and their unique replicators are eliminated.

- Replicators can spread like viruses from one vehicle to the next.

- The ‘vehicle world’ itself evolves.

5.1 Memes can be copied reasonably faithfully, occasionally mutate and confer an evolutionary advantage

I suggest that there are four types of memes which are critical to the survival of communities and therefore must be maintained and developed. I have characterised these as skills/technologies, knowledge, organisation and culture(mores).

Central to the human success story has been the ability to create new technologies and train succeeding generations how to apply them. The skills to make spears and bows and use them for hunting were passed on by hunter-gatherer families. In the Middle Ages, bread making skills were acquired and retained by generations of family bakers. In the modern era commercial firms retain a myriad of technical skills to ensure their competitiveness.

Knowledge includes all the information that the community retains. In agricultural communities, knowledge comprises an understanding of flora, fauna, the workings of nature and the effect of the passage of the seasons. In the Middle Ages, religions were an important source of knowledge; priests determined how to appease the gods, ask for help from ancient spirits and how to ensure a better, healthier future. In more modern times, knowledge includes valuable patents held by high-tech firms. The development of the sciences, particularly since the Enlightenment, has vastly improved the extent and accuracy of human knowledge. Since the first printed books and particularly following the development of the internet, much of this knowledge is held in common, accessible to all communities.

The ability of communities to create and maintain complicated organisation structures is unique to humans. The concept of organisation includes:

- accepted processes for reaching communal decisions.

- how subcommunities relate to the community as a whole and how to interact with the outside world.

- how leaders are selected and how they exercise their power in a community.

- how community activities are resourced and how commerce is managed.

A critical part of the concept of an organisational structure is the abstract concept of an ‘office’, a position in a community which has specific roles and responsibilities, independent of the individual that occupies it. This not only includes leaders like kings and chiefs but also intermediate administrative roles like judges or mayors as well as front line jobs such as inspectors or traffic wardens. When an office is vacant it can be filled by another individual and, as long as the selection process is seen as valid, their authority is accepted by the community as a whole.

I am going to use the word ‘mores’ instead of culture in this paper to avoid confusion. By mores I mean non-utilitarian behaviours and beliefs that operate to encourage community cohesion. They include superstitious beliefs, behavioural norms, taboos, sanctions and emotional responses. The definition also includes the common set of stories, ceremonies, song, dance and dress which celebrate group identity. Boyd(Boyd 2018) and many others have emphasised that it is the establishment of behavioural norms that allow individuals to successfully work together in a community. A common set of mores is vital if a community is to discourage genetically inspired selfish action against the interests of the community as a whole.

5.2 Communities survive sufficiently long to maintain and develop memes.

Our human ancestors were unique among mammals in their ability to engage in non-food gathering activities such as making clothes, tools, structures or ornaments. Such non-food items are not immediately perishable and can be traded and as such constitute an individual’s wealth. After the Neolithic Revolution, other durable items came to be considered as owned assets which could also be traded. This included mined minerals, metal goods, food surpluses and livestock. Later the concept of wealth expanded to include the ownership of land and slaves.

All humans who are not directly involved in agriculture or foraging have to be able to create or acquire sufficient wealth to trade for the food necessary for survival. Communities can own wealth as well as individuals. Though unrelated to memes, non-perishable wealth is heritable. Whereas the genetic effectiveness of a species can be measured by its population growth, the memetic success of a community, over the long term, can be measured by its wealth. Whilst the immediate objective of a community may not be wealth acquisition, its long-term survival is dependent on it. Successful communities create, acquire, maintain and develop wealth to increase their chances of survival.

A community’s meme-sets are maintained and developed by a combination of individual initiative, community consensus, and decisions of the leadership. In the case of a religion, most of its unique meme-sets are determined and preserved by priests themselves, rather than by the congregation as a whole. In contrast some communities have no leaders and their meme-sets are maintained by a high degree of social interaction. An example would be the English upper class in the early twentieth century. As a class they all attended the same schools and universities. They inter-married. The men held senior roles in government and industry. They had their own set of mores: they spoke with a distinct accent and dressed differently to the rest of the country. They also had a sense of imperialistic duty drilled into them at school. Having no leadership didn’t necessarily mean they couldn’t act as a group; they were more than capable of organising resistance if their privileges were threatened. The rejection by the House of Lords of the ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909, aimed at taxing wealth and inheritance, is but one example.

The timescales of memetic evolution are quite different from that of genetic evolution. Communities that survive over a thousand years, such as the Catholic Church, are relatively rare. The formation of the USA, which has had such an influence on the development of democratic government, only occurred 2 and a half centuries ago. Skipping forward to the modern era, Google has only been in existence just over 2 decades and yet its search engine has transformed the way society operates.

5.3 There is a ‘community world’ in which communities play specific roles

I am going to call this ‘community world’ the human interactive zone (HIZ). Communities operating in the HIZ display all the characteristics that one would expect from a memetic evolutionary process in which communities act in their own self-interest. Just as different species evolve to play a specific role in the natural world, many different types of community, as diverse as schools, religions and armies have evolved to play their role in the HIZ. To analyse this and to chart the evolution of the various types of communities it is necessary to classify communities according to their structure and function.

I am going to specify the most fundamental type of community as a community class. This is defined by its broad membership structure, how its members are selected and the degree of power that leaders have over the membership. Examples of community classes are: religions, whose membership consists of believers and the priesthood, firms with employees and shareholders. The most important modern community class is the state; this consists of citizens and a government that has absolute power to make decisions that affect all its inhabitants.

Community classes can be sub-classified in two main directions, according to either their organisational structure or their role in society. Thus, states can be categorised by their organisational set-up as dictatorships, democratic republics, constitutional monarchies and so on. Similarly, firms can be classified as being in the financial, manufacturing, service or retail sectors with further sub-classification possible according to their particular field of activity. Unfortunately, it is not possible to develop a community equivalent of the Linnaean taxonomy of animal species. In the same way that a full hierarchical Linnaean taxonomy of bacteria has not proved possible due to the relative ease of migration of DNA between different forms of bacteria, the ease of transmission of memes between communities has prevented the formation of a linear evolutionary path, necessary to form a hierarchy of taxons.

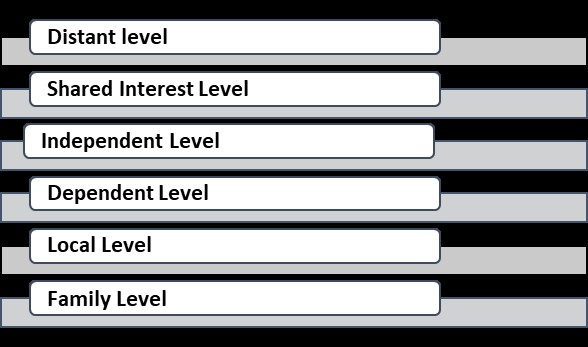

Each human has only one set of genes but has several different meme-sets derived from each of the communities that he/she belongs to. Whereas chimpanzees live in just one type of community, the band, humans are able to be members of many communities at the same time. These communities may operate independently or be dependent on communities operating at a higher level. This uniquely human characteristic has allowed humans to create the complicated multi-level societies that we have today. Figure 1 below defines six levels of human interaction.

Figure 1 the six levels of human interaction

The base level contains one class, the family; since humans acquired the ability to speak, the family has had the vital role of passing language skills on from generation to generation. Babies have the ability, using statistical learning techniques (Xu & Kushnir, 2013), to analyse the input from patterns of sound waves, aggregate them into words and associate them, initially with physical, and later with abstract concepts held by their parents. By this means a shared view of the world expressed in language is passed between generations. This ability to pass on concepts by language is the prime reason that human memetic evolution is so different from that of all other animals.

A community class operating at the independent level has the organisational power to impose its will on its members and is able to interact with other independent communities, largely free from external constraints. In early human history the only independent communities were bands of hunter-gatherers, tribes, tribal chiefdoms or states. They have been called societies by Patrick Nolan and Gerhard Lenski(Lenski and Nolan 2009). The term society, like community, is widely used in archaeology, anthropology and sociology with subtly different meanings. Nolan and Lenski define a society to be a politically autonomous organisation in which its members engage in a broad range of cooperative activities. I prefer to use the term polity for such communities and reserve the term society for the totality of the polity’s interactions.

Dependent communities are subgroups of independent communities that are reliant on the patronage of a polity. Examples are the army, the legal profession and the civil service.

Local communities are independent communities that operate within a polity, examples are firms and charities. If dependent communities are to compete and cooperate in a relatively frictionless manner, citizens and communities have to comply voluntarily with the mores and organisational rules of the governing polity. This includes both the moral norms of the polity and how policy is formulated, how the law operates, and how commerce is managed. This combination of the moral norms and the individual and polity, rights and responsibilities, represents a polity’s political culture.

The common interest level consists of voluntary associations of independent communities and those independent communities who have an affiliation because they share a common political culture. Modern examples of voluntary associations include the European Union and the North American Free Trade Association. Examples of common political cultures include Celtic tribes in Britain at the time of the Roman invasion, Catholic Europe in the Middle Ages or post-war Western Democracies. They might be considered as the equivalent of eco-systems where memes circulate freely between like-thinking communities.

There is a sixth level which I have called the distant level. This is the level where cultures clash and there a few exchanges of memes. In the past, community interaction between such communities has often been only for trade or war. One example would be the division between farming communities and the pastoralists in the first millennium BCE (states and empires regarded the pastoralists as ‘barbarians’). Another example would be conflict between Catholic Europe and Islamic countries at the time of the crusades. The League of Nations as it existed before the Second World War could be classified as a distant community; it included democratic, fascist and communist states.

Throughout most of human history there has been a level, above the distant level, in which communities were unaware of each other’s existence. The scope of human interaction only grew as transportation technology improved. Ptolemy’s famous map of the world shows that, by 150 CE, Europe, North Africa the Middle East, India and China were aware of each other’s existence. America and Europe only became fully acquainted after the fifteenth century and the exploration of sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania by the West only occurred in the last two hundred years.

The appendix gives examples of community classes and their levels of operation, for societies that have evolved since the Neolithic Revolution.

5.4 Communities interact with each other and mutually affect each other

Communities interact in one of three ways; they can compete, co-operate or co-exist. Cooperation involves building alliances and often leads to more effective operations, increased trade and a specialisation of roles. Examples of co-operation include: the distribution of goods from suppliers to manufacturers, universities sharing the workload on big research projects and charities taking on specific roles at the scene of natural disasters.

Similar types of communities, however, usually co-exist or compete. Co-existence involves setting up and agreeing a sphere of influence. Examples are market cartels, peace treaties between countries or simply neighbours living next to each other. Co-existence can be a stable situation but, as it does not change the status of either party, is not an evolutionary process.

Competition between communities is either for membership, status or reward. For example, religions compete with other religions to gain congregations, football teams compete to win trophies, and firms compete to sell their products. Those communities with the most effective combination of skills/technology, knowledge, organisation and mores will thrive. When the nature of the competition becomes so serious that weaker communities cease to exist, then the evolutionary process of survival of the fittest commences; only those communities that have developed the most effective memes will endure.

Richerson et al (Richerson et al., 2016) have proposed warfare, commercial competition between economic organisations and religious competition as the three main drivers of cultural(memetic) evolution. I will call these three competitive processes: violent, commercial and popular. Popular competition takes place between political parties in addition to religions. If unsupported by the state, communities formed as a result of popular competition require voluntary contributions from their membership to ensure survival. Trade and commerce have become an increasingly important driver of memetic evolution since the Industrial Revolution. Violent competition between human communities, on the other hand, has been present throughout the existence of our species.

This paper maintains that the necessity and/or desire for communities to acquire wealth underpins each of these three competitive processes. There are basically only four ways of communities acquiring wealth: by stealing, by extortion (demanding money with menace), voluntary contribution or by commercial transaction. Stealing or extortion involves violence or the threat of violence. The desire to increase voluntary contributions is a driver of popular competition. Commercial transactions are the basis of competitive trading between firms.

5.5 There is a competitive process in which some communities and their unique memes are eliminated

It goes without saying that many states and tribes and their associated languages and customs have disappeared through the course of history. It is true that archaeology and written records give us some impression of the memes of ancient communities, but the depth and understanding of life in ancient times has largely been lost. Much of the local culture of individual villages has disappeared. The number of tribes or villages that routinely wear a distinctive dress is diminishing. Ancient religious ceremonies, of extinct tribal ethnicities such as the Gauls or defunct states such as Babylon, are no longer practiced and the organisation and superstitious knowledge of their priesthood is no longer understood. Skills and technologies have been lost as well, very few of us would have the skills and knowledge to survive as a Stone Age hunter-gatherer or a mediaeval peasant.

5.6 Viral Effect

Memes that improve the survival prospects of a community are spread by diffusion between communities or by the military success of the community itself. The diffusion of memes between communities is analogous to the spread of viruses between life-forms. But whereas the effect of externally communicated viruses on life-forms is mostly detrimental, communities actively acquire memes from other communities to increase their effectiveness. Skills and technologies are more easily transmitted than organisation and mores, as the people with those skills can migrate between communities. Even so, in ancient societies many critical skills took centuries to become commonly used by states; an obvious example being the 400 years it took for printing technology with moveable typefaces to transfer from China to the West.

A modern example of the viral effect of memes results from the formation of the British Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As a consequence, large parts of North America and Oceania are now populated by people of British descent maintaining many aspects of the culture of the home country. In the nineteenth century British ideas of constitutional monarchy and industrial development were copied by many European states in order to enhance their wealth, power, and military and commercial competitiveness. As an unintended by-product, the British language has become a global lingua franca, and football, golf, rugby, cricket and several other sports, developed in Britain, are played throughout the world.

5.7 The human interactive zone evolves

It is indisputable that the shape and structure of the HIZ has changed dramatically since the start of the Holocene. Many have tried to classify the steps in this development. Ancient societies were traditionally classified according to their technology into the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages. Elman Service(E. Service 1971) identified five steps based on the development of social organisation: hunter-gatherer bands, tribes, chiefdoms, primitive states and civilisations. Gerard Lenski in his book Ecological Evolutionary Theory (Lenski 2005) categorised six primary types of human society based on their mode of subsistence: hunter-gathering, simple and advanced horticultural, simple and advanced agrarian and industrial. He defined the distinction between horticulture and agriculture by the use of the plough; horticulturists were assumed to be more likely to leave fields fallow or adopt a ‘slash and burn’ farming strategy in order to maintain the productivity of the land. The difference between simple and advanced reflected their use of metals. Like the evolution of communities, the evolution of the HIZ is certainly dependent on the evolution of organisations and technologies. However, I propose that there is a more fundamental force at work: the desire for individuals and communities to acquire wealth.

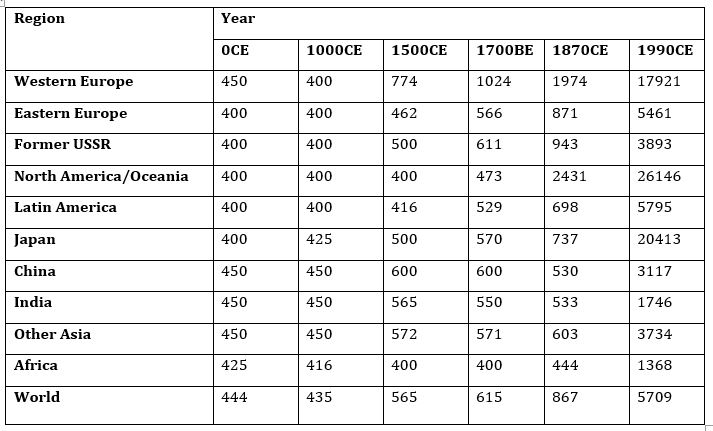

Taking a broad view, there have been 2 main phases in the rate of wealth creation since the Neolithic Revolution. In the first, or agrarian phase, which lasted from the Neolithic Revolution until the nineteenth century, the principle source of wealth creation was farming and herding. In the second, or industrial phase, the main source of wealth creation was commercial activity. The dramatic difference in the scale of wealth creation between the two phases is illustrated in table 1 below which is extracted from The World Economy by Angus Maddison(Maddison 2001). It shows that at the start of the first millennium, when the Han dynasty of China was near its peak and Rome had its first emperor, there was very little difference in output per capita across the world. Maddison estimates that Chinese GDP/capita was just 12.5% above areas such as Japan and North America which were largely tribal. In the succeeding thousand years to 1000CE the average levels of wealth scarcely changed. In the following period to 1500CE, improved agricultural methods and increased levels of commerce raised output significantly in Asia and West Europe. Thereafter the Industrial Revolution took hold in Europe and North America. Wealth/capita increased much more rapidly in ‘Western Democracies’ and created a huge disparity in output between richer and poorer countries.

Table 1 GDP/capita at 1990 $ prices according to Maddison

Table 1 GDP/capita at 1990 $ prices according to Maddison

Given that wealth creation levels, measured as GDP/capita, were very similar across the world until 1500 CE, why was there such a difference in types of polity? The answer seems to lie in the degree of wealth extraction available to the leadership.

The fundamental basis of memetic evolution is that each community acts in its own self-interest. However, there are qualifications to this idea because it is a community’s leadership that determines community policy and thus, plays a key role in its success or failure. As polities became larger, leaders acquired more power, which gave them the opportunity to exploit this power for their own benefit. There is a natural conflict between individual ambition and community objectives. This is the point where memetic evolution clashes with genetic evolution, when the drive for the leader to advance his own and his family interests can conflict with the greater good of society as a whole.

Within every polity, decisions have to be taken on how wealth is extracted and redistributed; each individual and each sub-community will vie for their share. It can be predicted that the degree of personal benefit garnered by leaders and their supporters, will correspond to the extent of the untrammelled power they exercise over the rest of the polity.

5.7.1 Agrarian polities

I propose there were four broad stages of wealth extraction in agrarian polities which I have characterised as durable, taxable, transferable and portable.

5.7.1.1 Durable wealth, tribes and tribal chiefdoms

Hunter-gatherer communities had few durable assets, food was perishable, stone tools had to be regularly replaced and housing easily assembled. This changed as agricultural technology developed. Domesticated animals provided a long-lasting supply of nourishment. The development of pottery allowed grain to be stored for longer periods. Access to individual plots of land became valuable and heritable. In addition, families were able to specialise in non-food gathering skills such as weaving or metal working to make items that could traded.

Durable wealth created by agrarian societies could be stolen; raiding other communities became more lucrative with the acquisition of animals and grain. In addition, instead of killing their adversaries, raiders could acquire slaves to work their land. The increasing risk and reward from raiding forced villages to cooperate in attack and defence. A new community class, the tribe, was formed consisting of people who cooperated with each other over a wide area.

We can assume that the size and geographical spread of cooperating villages meant that leadership by consensus was no longer practical. Gavrilets et al (Gavrilets, Auerbach, and Van Vugt 2016) show the ‘strong benefits of leadership particularly when groups experience time pressure and significant conflict of interest between members.’ Azar Gat in his book War in Human Civilisation (Gat, 2006) asserts that the first leaders of tribal polities were ‘big-men’ who exercised power on the basis of the strength of their personality.

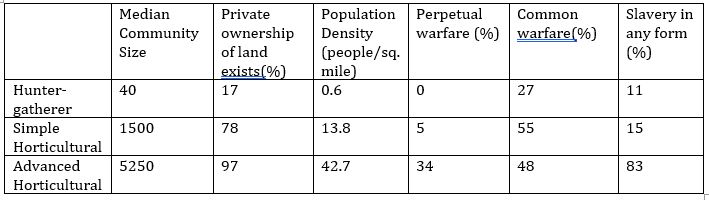

Table 2 below is taken from Nolan and Lenski’s book, Human societies(Lenski and Nolan 2009) and is based on their analysis of George Peter’s Ethnographic Atlas of pre-industrial societies that survived into the modern age. It shows clearly that as population densities increased, warfare became more common. Nevertheless, for simple horticultural societies the possibility for differential wealth acquisition appears to have been limited. This is shown by Mulder et al (Mulder et al. 2009) in which they show that the Gini coefficients of comparable horticultural societies are scarcely any different to those of hunter-gatherers.

Table 2 Comparison of pre-industrial communities that survived into the modern era.

Table 3 also shows that in advanced horticultural societies, those that used metals, the levels of land ownership and slavery were more prevalent than in simpler communities. Advanced horticultural tribes were also larger and more committed to war. Azar Gat Documents in War, how big-men became chiefs with a retinue of young warriors, eager to share the spoils of war. These young warriors could bully others in the tribe, giving the chief the power to command and extract tributes. When this occurs, tribes are known as tribal chiefdoms and have a much greater stratification in wealth and income.

Never-the-less wealth was still accumulated personally. The chief’s wealth was passed onto his family. It appears that while there were structures and areas of land that were held in common for the tribe, the office of the tribal chief retained little durable wealth.

5.7.1.2 Taxable wealth and agrarian states

In his book Origins of the State and Civilisation(E. R. Service 1975), Elman Service speculates on the necessary conditions for state formation. He rejects warfare and conquest, irrigation and agricultural intensification, economic growth, and urbanisation to be a sufficient cause, even though many of these characteristics are present in early states. James C. Scott in his book Against the Grain(Scott 2017) makes the case for the cultivation of grains to be the critical factor. He suggests that this is because grain harvesting is relatively easy to tax. The early state polities, in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, were all associated with the harvesting of grain. Grains unlike other sources of protein such as tubers or legumes have to be harvested at a predictable time. Grain is also less bulky and more easily measured by volume. Harvesting can therefore be monitored and measured by tax inspectors and the state’s share can be extracted at source.

In states, leaders could command; voluntary service given by tribes became compulsory, with corvée (forced) labour and military call-up, and optional gifts were converted into regular taxes. To collect these taxes required organisation, planning and record keeping. These early states are all associated with the development of writing skills. A new community class of administrators or bureaucrats mastered these writing skills. Over time these skills developed into a full system of communication and bureaucrats came to play a major role in state management.

States spent some of this tax income on symbols of power such as palaces and mausoleums as well as major capital works, such as grain stores, defence systems, canals and bridges. Some of which have survived until modern times and constitute the legacy of these first states, often perceived as evidence of civilisation.

The leaders, commonly referred to as kings, held wealth as an office of the state and as such it could be passed onto the next king. The state was not the only community class to obtain wealth in a taxable agrarian state. James C. Scott shows evidence that taxation in the Fertile Crescent might at first be associated with some sort of religious tribute. That the priesthood was wealthy is attested to by the size of the temple at Uruk, which was larger than the Parthenon at Athens even though it was built 3000 years later.

As writing and bureaucracy became more commonly used, rents could be collected in the same way as taxes. Privileged families acquired land holdings and the associated rental income, as peasants failed to retain their independence as a result of failed debt repayment, illness or misfortune. A new community class of aristocrats evolved who owned land and whose principal income was rent.

5.7.3 Transferable wealth and empires

In advanced agrarian states, rents and taxes became the principal regular source of income for the wealthy. After the methods and bureaucracy of collecting rents and taxes became fully established, ownership of the land and its income could be transferred easily to another individual. The spoils of war had up to this moment been plunder, rape and the capture of slaves but now a more permanent income could be obtained by acquiring the ownership rights of land. Local rulers could be replaced by centrally appointed governors, and bureaucrats could continue to raise taxes and rents from the peasantry.

The inherent logic of the violent competitive process is that those communities that mobilise the most effective warriors will be the most successful. A new community class of full-time professional soldiers (and sailors) evolved to conquer other countries and gain the income from peasants working the land. A process of state consolidation began so that by the first millennium BCE, huge empires were formed in Eurasia, in particular in China, India, the Middle East and Europe. That this was the result of war is a matter of historic record.

Peter Turchin et al (Turchin et al. 2013) have shown by modelling historical data that violent competition between polities, that rely on farming in relatively flat landscapes, inevitably leads to a consolidation of power. Eventually this would lead to the elimination of tribal farming polities in large parts of Eurasia. However tribal societies still maintained their power in the steppes, forests and mountains right into the second millennium CE. Strongly motivated by the desire to steal and extort wealth from the neighbouring states, they frequently formed huge confederations of their tribal ethnicity and were more than a match for the state armies.

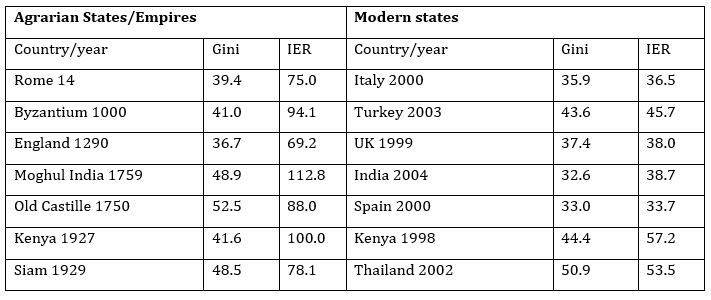

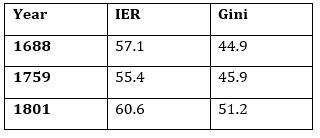

As predicted above, it does appear that, in advanced agrarian polities (states and empires) in which emperors, kings, aristocrats, priests and some bureaucrats had immense unchecked power, there were high levels of wealth extraction from the peasantry. In their 2011 paper Milanovic et al (Milanovic, Lindert, and Williamson 2011) have attempted to measure the degree of extraction by an inequality extractive ratio (IER). An IER of 100 implies that the poor have only a minimum subsistence income and all their surplus output is extracted by the richer members of society. A sample of their findings for pre-industrial and modern-day states is given below in table 2. Even though many of the Gini coefficients (and therefore inequality levels) were similar, the level of extraction was much higher in agrarian states, with IERs of 75- 110 for pre-industrial polities compared to IERs of 33- 51 for modern states.

Table 3 Estimated Gini coefficients and IERs (Inequality Extractive Ratios) for pre-industrial and modern economies

5.7.4 Portable wealth and evolution due to Commerce

Agriculture was the main source of wealth creation for agrarian societies, but mining, manufacturing and trade has always been present as an additional source of wealth acquisition. Throughout early history trade had to be conducted by barter. The development of trade tokens or coinage made from gold, silver and/or bronze in Eurasia in the first millennium BCE transformed the nature of commerce, eliminating the inefficiencies of barter. It simplified the calculation of profit and loss and allowed wealth to be stored in a portable manner.

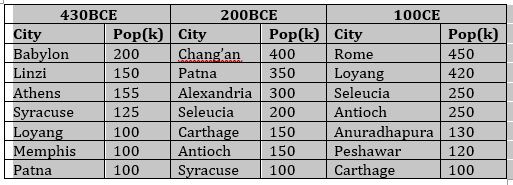

That this improved the level of commerce is evidenced by the number of people that were able to live in urban environments. Taking information from Chandler’s book Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth (Chandler 1987), it appears that before coinage was freely circulating, cities approaching 100k inhabitants were extremely rare. Chandler mentions just three: Ur 65k in 2000BCE, Avaris(Egypt) 100k in 1600BCE and Niveveh, 120k in 650BCE. All these were centres of thriving states. Table 4 shows a dramatic change after 500BCE, when coinage was freely circulating in Eurasia, with several cities with over 100K inhabitants coming into existence.

Table 4 Cities with a population over 100k (430BCE-100CE) according to Chandler

Table 4 Cities with a population over 100k (430BCE-100CE) according to Chandler

Other estimates of Chandler’s figures have since been proposed and new centres of population have been identified. Nevertheless, the general shape of table 4 remains. After the invention of coinage, not only did the centres of large states grow significantly in size, but new centres of commerce such as Athens, Syracuse, Alexandria, Antioch and Carthage became major centres of population.

5.7.2 Industrial societies

5.7.2.1 Companies, wealth investment and capitalism

Right up until the nineteenth century manufacturing had a less important role to play in wealth creation than agriculture. This is evidenced by the percentage of people able to live in urban centres. Lenski states that, ‘rarely, if ever, did all of the urban communities of an advanced agrarian society contain as much as 10 percent of its population.’ The great empires of China and Rome, for example, were overwhelmingly based on a rural economy. This changed after the Industrial Revolution in the UK in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Central to the transformative effect of the Industrial Revolution was the evolution of a new community class, the joint stock firm. Joint stock firms raised capital by issuing share certificates to investors. Dividends were paid, and shares could be traded on a stock exchange. Those firms that thrived could raise more capital and grow. Those that failed, ceased to exist. Investments in joint stock firms could increase in value. In industrial societies, income from investments became an important source of wealth. Technical development was driven forward as firms competed with each other in an evolutionary wealth creation process, commonly known as capitalism.

The characteristics of a modern joint stock firm were pioneered by the VOC (Vereenigde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie) in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. When, in the eighteenth century, manufacturers in Britain developed new processes for generating power, making iron, and spinning and weaving textiles, the right community vehicle was in place to drive forward the Industrial Revolution.

The social science of microeconomics focusses on the trading of products within a market structure. In economic theory, if humans make their decisions absolutely rationally and there is perfect competition, mathematicians have shown that the market will reach some sort of equilibrium(Debreu 1959). In my view the market place is more realistically envisioned as firms competing with other firms in an evolutionary process whereby excellent firms thrive by developing, the best technologies, expanding their sector knowledge, creating an efficient and effective organisation, and encouraging the workforce to adopt appropriate mores. Adam Smith’s famous phrase, ‘it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest’, is often construed to support the view that economic success is based on individuals acting in their own self-interest. It can be more realistically envisioned as an expression of the benefits of memetic evolution by commercial competition between family firms. The ‘invisible hand’ that promotes ‘an end which is no part of his intention’, is an observation of evolution in action.

5.7.2.2 Nascent industrial societies

Hitherto those states which were focussed on Commercial activity, had concentrated on trading rather than manufacturing. As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the United Kingdom became the first true industrial society. To be successful, industrial societies also needed to have a political culture that supported commerce. Great Britain had, by a series of evolutionary accidents, evolved a unique political culture that included democratic processes, and an independent legal system. This culture allowed manufacturers and traders to both influence government policy to support commercial development and have the legal backing to support the operations of commerce, including regulations for limited companies, contracts, bankruptcy and debt collection.

There is no evidence that industrialisation itself led to a less extractive society. Table5 below, also from Milanovic et al (Milanovic, Lindert, and Williamson 2011), shows that at the start of the Industrial revolution the levels of extraction in the UK actually grew. The poor slum conditions in industrial towns in the nineteenth century testify to the fact that workers remained at near subsistence level incomes with few possessions. Capitalism is a process in which firms act in their own and their leaders’ self-interest. For capitalism to work for the good of all, some democratic controls need to be put in place to ensure the ‘invisible hand’ works for the public good. In the nineteenth century, there are many examples, in both Britain and the USA, of firms over-rewarding their executives and shareholders, exploiting their workers, abusing their market position and paying as little tax as possible. Adam Smith himself warned that ‘in any particular branch or trade of manufacturers, [their interest] is always in some respects different from and even opposite to that of the public’.

Table 5 Gini and IER for England and Wales (1688- 1801) (Milanovic et al)

Table 5 Gini and IER for England and Wales (1688- 1801) (Milanovic et al)

The memes necessary to start the industrial revolution spread rapidly to Western Europe and North America in the late nineteenth century. Table 1 shows that, for the first time, huge differences in wealth appeared between North America and Europe compared to the rest of the world. China, India and much of Asia and Africa failed to adapt to the new technologies fast enough and became vulnerable to superior military might. Britain, France, Germany, USA and Italy all vied with each other to create global empires. The Japanese had the foresight to adopt the memes of industrialisation at the end of the nineteenth century, elsewhere few areas of Asia and Africa escaped Western Domination.

5.7.2.3 Consumer societies and token wealth

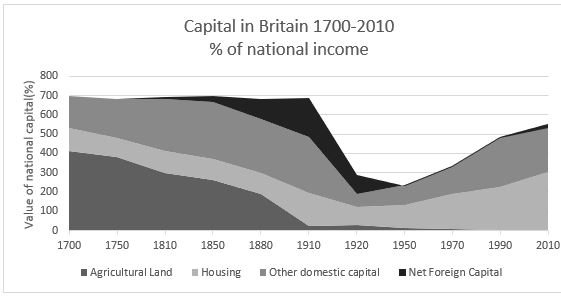

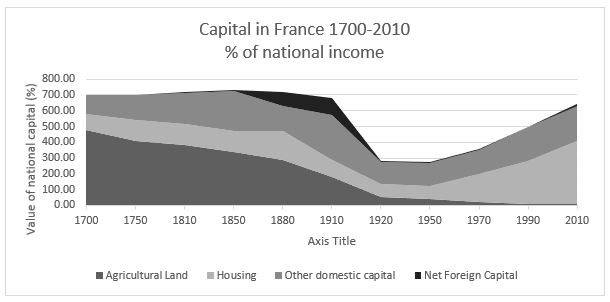

In Europe, industrialisation changed the balance of power between the socio-economic classes. As Piketty explains in Capital, (Piketty 2013) investment income grew in importance at the expense of rental income. He Illustrates this by observing that the ratio of the value of agricultural land to national income in the UK fell from 400% in 1700 to less than 50% by 1910 (Figure 2). In France the decline was from 480% to less than 100% by 1920(Figure 3). The basis of power of the landed classes in agrarian societies was unsustainable. Right across the world kings, emperors and priests lost power, most notably in five traditional empires: Germany (1918), Austria-Hungary (1918), Russia (1917), China (1912), and Ottoman (1922)

Figure 2 Changes in capital in Britain according to Piketty

Figure 2 Changes in capital in Britain according to Piketty

Figure 3 Changes in capital in France according to Piketty

Two new community classes, political parties and trade-unions, evolved in countries with a democratic capitalist political culture; both were to have a huge influence on the balance of wealth between the socio-economic classes. They gave the urban poor, for the first time, some clout in how wealth was distributed. As a result, democratic capitalist societies curbed some of the inherent negative impacts of capitalism. Health and safety legislation was enacted, legal protection was given to trade-unions, cartels were prohibited, profits were taxed and there was some redistribution of wealth using income and inheritance taxes.

In the West, the inter-war years saw the birth of the consumer society. Mass-production techniques reduced prices sufficiently to allow society as a whole to benefit from industrialisation. Evidence is anecdotal, but it is clear that many houses had running water, radios, electric lighting and gas cookers and individuals owned new forms of transport, if not a car then probably a bicycle. This level of wealth invested in consumer durables was simply not present in poor households in pre-First World War societies.

Paper money had been used in China as long ago as in the Tang dynasty in the 7th century. Bills of Exchange were used in Europe in the Middle Ages and European banks began to issue promissory notes from the 16th century onwards. However, the value of these notes had been always related to the value of precious metals. The level of state spending in the First World War forced many states, including Britain and Germany, to issue their first state sponsored banknotes and abandon the guarantee of convertibility of notes into gold. These banknotes represented a new form of token wealth by which states could now create money at minimal cost. Gold coinage was withdrawn from circulation and ‘silver’ coins were replaced by an amalgam of copper and nickel. Mediaeval States had been able to devalue their currency by debasing the coinage, but the introduction of token wealth gave states a completely different level of responsibility for managing the level of currency in circulation. Macro-economic management failed catastrophically in Germany, with hyper-inflation in 1923, and even more seriously across the World in the Great Depression in the 1930s. These put into doubt the effectiveness of the meme-set of the democratic political cultures of Great Britain and the USA. The inter-war period saw several experiments in alternative political cultures that also encouraged industrialisation, including Communism, Fascism, and Socialism.

5.7.2.4 Redistributed wealth and Welfare state societies

The emergence of fully democratic states and the creation of a more egalitarian society in West Europe was only really achieved after the First and Second World Wars. This is explained at length in Scheidel’s book The Great Leveller (Scheidel 2017).

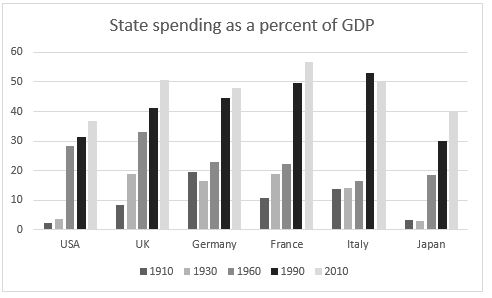

A democratic state’s implied purpose is one of supporting all its citizens, not just the elite. The welfare state that developed in North America, West Europe, Japan and Oceania after the Second World War was the first modern society in which there was a redistribution of income away from the rich. Piketty shows that in the West the period from 1950 to 1980 was by far the most egalitarian in the last 2 centuries (Piketty 2013). The negative effects of capitalism were curbed, state sponsored education expanded dramatically and the state became heavily involved in health and social welfare. Before the First World War state spending in most countries had been less than 10% of GDP. After the Second World War, state spending in economically advanced countries rose to 35–55% of GDP. This is illustrated in Figure 4 for USA, Japan and 4 European countries

Figure 4 State spending as percent of GDP

Figure 4 State spending as percent of GDP

Source Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (2016-10-18). “Government Spending”. Our World in Data

The state now had enormous powers of patronage and state agencies now employed a significant proportion of the population. Social services were improved, state-supported health care schemes came into existence, and education opportunities were expanded for all. Class divisions became less obvious and social mobility improved.

In the West the manufacturing and service industries expanded so much that farming became a minority form of employment. The urban population now greatly outnumbered the rural population. Huge differences in wealth per capita remained between the wealthy ‘West’ and the rest of the world.

5.7.2.5 Accelerating evolution, the Global Industrial Society and electronically transferable wealth

Genetic evolution of mammals is a necessarily slow process, being dependent on random mutations in DNA. Memetic evolution should be faster as it depends on the speed of generation and transmission of ideas. Indeed, humans with their advanced abilities to transmit memes have reshaped the eco-systems of much of Earth’s arable land in just 10,000 years since the advent of the Neolithic revolution.

However not only is memetic evolution a faster process, it has accelerated in line with the improvement in communication technology. This is apparent in that classic measure of a species success, population growth. It took approximately 200,000 years, until circa 1800 CE, for the level of human population to reach 1 billion. In the succeeding 2 centuries, since the Industrial Revolution, it has passed 7.5 billion(Livi-Bacci 2007).

Whereas much academic work on cultural evolution has concentrated on earlier types of societies, it is at the present time that memetic evolutionary forces are at their most dynamic. Around 1990, technological developments, based on instantaneous data exchange and the electronic transfer of wealth, further accelerated the rate of evolutionary change. For want of an established label, I have called this the Information Revolution. In this Information Revolution, as described by Kelly in What Technology Really Wants (Kelly 2011), the internet and the mobile phone have transformed communication; information storage and access allows us to monitor and control minute aspects of our lives; bio-technology is improving even further our ability to remain alive in reasonable health; and robots are becoming ever more capable of taking on human tasks. Further, all these technological advances are happening on a global scale. Multi-national firms now source their products from the cheapest locations and deliver fantastic technologies at affordable prices.

In this globally interactive world, new types of communities have evolved to become major players on the world stage. These include social media companies like Twitter and Facebook, coordinators of independent service operators like Uber and Airbnb, and operators of search engines such as Google.

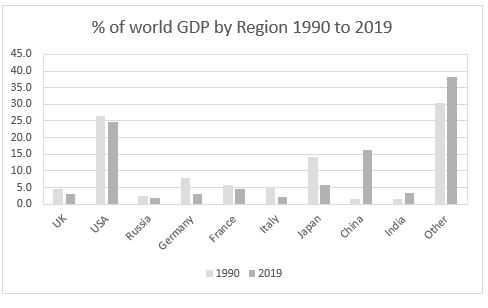

The memes to support a vibrant industrial economy have now spread to many other states outside of ‘Western Democracies’. The Chinese have achieved an astonishing transformation in economic output. In 1990 they accounted for just 1.6% of world GDP; by 2019 they had become the second largest economy in the world and accounted for 16.2% of output. Brazil India and many other nations are also improving their levels of wealth. Figure 5 shows that the share of world output of nations excluding the USA, UK, France, Germany, Italy and Japan has increased from 48% to 61% in the period from 1990 to 2019.

Figure 5 Share of the world’s GDP by Country (1990, 2019)

Source OECD

There has been no direct confrontation between major powers since the Korean War. Violent competition as a source of evolutionary change has momentarily ceased to be globally significant. It is commercial competition between multi-national firms that is now the main driver of memetic evolution. Companies such as Google, Facebook, Huawei and Amazon have risen from nothing to become global powers who affect all our lives.

Technologies are developing so fast that human culture and organisation are struggling to adapt. In this globally interactive world, since the USA has stepped back from global leadership, no state is in control of events. Communities which operate at the independent level of society: multi-nationals, international NGOs, religions, global elites and states, compete and cooperate on a global scale solely on the basis of mutually agreed protocols.

In the West, multi-national companies and rich elites are accumulating wealth, power and influence at the expense of states and their citizens. It is well documented that many of the negative aspects of uncontrolled capitalism are re-emerging. Executive salaries are sky- rocketing(Piketty 2013). The gig economy has created a new underclass of poorly rewarded labour(Graham, Hjorth, and Lehdonvirta 2017). Multi-nationals are avoiding paying tax by routing trades through tax havens(Shaxaon 2012). Democracies are being undermined by the power of money from big business(Potter and Penniman 2016).

Figures 2 and 3 show that wealth held in housing stock has grown in importance since 1980 and is replacing agricultural land as a source of rental income. Inherited wealth is again creating a new rich elite; levels of inequality are now approaching those that existed before the First World War.

China and Russia have developed successful alternative political cultures to democratic capitalism. These have allowed former communist elites to retain their wealth and power. These ex-communist countries are isolating themselves from the free flow of global information and using new technologies to establish a greater level of state control over their citizens.

However the political situation develops, and whatever new communities and memes evolve, there is one evolutionary effect that seems inescapable, the effect on the environment of growing levels of human population and wealth. Population levels of all other species expand until limited by the natural resources available. Up to now, by the judicious use of technology, human population has continued to grow. World population has tripled since the end of the second world war, to over 7.5 billion. According to the UN, it will reach 11 billion by the end of this century. There are real doubts whether continuing economic growth is sustainable(Pilling 2018). We are already seeing the effects of climate change, environmental degradation and a huge loss of biodiversity as we convert nature to arable land and pollute the environment. According to a recent paper(Bar-On, Phillips, and Milo 2018), humans and their domesticated animals now account for 97% of the biomass of all mammals on Earth. We have changed the very nature of the planet to suit our needs, so much so that geologists have deemed that we have entered a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. If the climate scientists are right the Anthropocene will herald an era in which environmental degradation will increasingly impinge on the memetic evolutionary process.

-

Conclusion

Based on six criteria, this paper claims that the development of human society exhibits the characteristics of an evolutionary process in which memes are replicators and communities are vehicles. This is a parallel process to genetic evolution, but is much more dynamic; it has been responsible for most of the advances in the human condition since the start of the Holocene. The effects of the memetic evolutionary process can be traced both in the phylogenetic development of memes, the emergence of new community classes, the formation of new types of society and the levels and types of wealth created.

Memetic evolution also explains many of the unique aspects of human development, such as:

- Why the human evolutionary process has been so different from that of all other animals

- Why wealth acquisition plays such an important role in human societies

- Why human societies have a tendency to become unequal

- Why the population of humans has recently expanded so rapidly

- Why the tribal instinct is so strong

The rate of human evolution is accelerating. New technologies are being developed, new cultures are evolving and new types of communities are being formed at a faster rate than ever. Understanding how the forces of evolution act on society is becoming a critical factor in the human struggle for survival. The study of memetic evolution is important not just from an academic viewpoint. It also provides a framework for understanding events in today’s world. If the drive for wealth acquisition is a fundamental aspect of human behaviour, this poses many problems for society as a whole. A society, which pursues wealth acquisition irrespective of its effects on the environment or the level of income disparity, is one which most rational people, interested in prolonging the long-term health of our species, would like to avoid.

Scientific confirmation of the memetic evolutionary process would offer mankind a means of understanding its impact and provide an opportunity to shape the direction it is taking us. We will need to find mechanisms which encourage different behaviours if humans are to be clever enough to become the first animal to purposely alter the direction of evolution.

Appendix 1 Examples of Societies and the community classes contained within them

The purpose of the following is to provide an overview of the community classes and their operating level for societies, that have evolved over human history. The list is not complete and I suspect the analysis is not wholly accurate. However, I hope that the format will be found useful and others can use and develop it as an aid to further work.

Hunter-gatherer societies

Level 4 Band

Level 5 Neighbouring bands speaking the same dialect

Tribal Societies

Leadership Big-men

Level 2 Village

Level 3 Clan

Level 4 Tribe,

Level 5 Tribal Ethnicity

Level 6 Surrounding polities

Chiefdom Societies

Leadership Chief

Level 2 Village

Level 3 Clan, Warriors

Level 4 Tribe

Level 5 Tribal Ethnicity, Priesthood

Level 6 Surrounding polities

Example Celtic tribes in Britain in the 1st century BCE

Agrarian State Societies

Leadership King

Level 2 Village, Town

Level 3 Clan, Priesthood, Aristocracy, Administrators

Level 4 State

Level 5 Other surrounding polities

Example Ur in the third millennium BCE

Empire Societies

Leadership Emperor

Level 2 Villages, Towns, Cities, Popular Religions, Trades

Level 3 Clan, Priesthood, Aristocracy, Administrators, Army

Level 4 Empire

Level 5 Other surrounding states and empires

Level 6 Other polities

Example the Roman Empire in the first century CE

Feudal Societies

Leadership King

Level 2 Villages, Cities, Guilds, Local Barons

Level 3 Administrators, Royal Appointees

Level 4 Kingdom

Level 5 Religion, Other Kingdoms sharing the same culture

Level 6 Other polities

Example England in the fourteenth century

City States societies

Leadership Oligarchy

Level 2 Trades, City Sections, Merchant Families

Level 3 Administrators, City Priesthood

Level 4 City State

Level 5 Other City States sharing the same culture, Religion

Level 6 Other states

Example Corinth in the fifth century BCE

Nation State Societies

Leadership Elected/ Dictatorship

Level 2 Local governments, Firms, Charities, Political Parties, Socio-economic classes, Clubs

Level 3 State agencies, Administration of overseas dependencies

Level 4 State, Religions

Level 5 Other Western states

Level 6 Other states

Example France in the late nineteenth centuries

Welfare State Societies

Leadership Elected

Level 2 Local government, Firms, Charities, Political Parties, Socio-economic classes, Clubs

Level 3 State agencies, State firms

Level 4 State, Religions, Multi-nationals, International NGOs

Level 5 Other Western states, EU, Communist States

Level 6 Other states, UN

Example Britain in the 1980s

Global Industrial societies

Leadership Elected/ Dictatorship

Level 2 Local government, Firms, Charities, Political Parties, Socio-economic classes, Clubs

Level 3 State agencies, State firms

Level 4 State, Religions, Multi-nationals, International NGOs, Global Elites

Level 5 Other ‘Western’ states, EU, Elite capitalist countries

Level 6 Other states, UN

Example Germany in 2010

References

Bar-On, Yinon M, Rob Phillips, and Ron Milo. 2018. “The Biomass Distribution on Earth.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (25): 6506–11. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711842115.

Boyd, Robert. 2018. A Different Kind of Animal – How Culture Transformed Our Species. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boyd, Robert, and Peter J. Richerson. 2010. “Transmission Coupling Mechanisms: Cultural Group Selection.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365 (1559): 3787–95. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0046.

Chandler, Tertius. 1987. Four Thousand Years of Uban Growth: A Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: The Edward Mellein Press.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. 30th ed. Oxford, New York: Oxford Univesity Press.

Debreu, Gerard. 1959. Theory of Value. New York: Wiley.

Dennett, Daniel C. 2017. From Bacteria to Bach and Back. New York: W. W.Norton and company.

Gavrilets, Sergey, Jeremy Auerbach, and Mark Van Vugt. 2016. “Convergence to Consensus in Heterogeneous Groups and the Emergence of Informal Leadership.” Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29704.

Goodall, Jane. 1988. My Life with Chimpanzees. Byron Press Visual Publication Inc.

Graham, Mark, Isis Hjorth, and Vili Lehdonvirta. 2017. “Digital Labour and Development: Impacts of Global Digital Labour Platforms and the Gig Economy on Worker Livelihoods.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 23 (2): 135–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258916687250.

Henrich, Joseph. 2004. “Cultural Group Selection, Coevolutionary Processes and Large-Scale Cooperation.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 53 (1): 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(03)00094-5.

Henrich, Joseph, Jean Ensminger, Richard Mcelreath, Abigail Barr, Clark Barrett, Alexander Bolyanatz, Juan Camilo Cardenas, et al. 2010. “Markets, Religion, Community Size, and the Evolution of Fairness and Punishment.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 327 (5972): 1480–84. http://science.sciencemag.org/.

Kelly, Kelvin. 2011. What Technology Wants. New Yrok: Hudson Press.

Lenski, Gerhard. 2005. Ecological-Evolutionary Theory Principles and Applications. Paradigm Publishers.

Lenski, Gerhard, and Patrick Nolan. 2009. Human Societes An Introduction to Macrosociology. 11th addit. London: Paradigm Publishers.

Livi-Bacci, Massimo. 2007. A Concise History of World Population. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishig.

Maddison, Angus. 2001. The World Economy A Millennial Perspective. OECD.

Mesoudi, Alex, Andrew Whiten, and Kevin N. Laland. 2004. “PERSPECTIVE: IS HUMAN CULTURAL EVOLUTION DARWINIAN? EVIDENCE REVIEWED FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES.” Evolution 58 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01568.x.

Milanovic, Branko, Peter H. Lindert, and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 2011. “Pre-Industrial Inequality.” Economic Journal 121 (551): 255–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02403.x.

Mulder, Monique Borgerhoff, Samuel Bowles, Tom Hertz, Adrian Bell, Jan Beise, Greg Clark, Lla Fazzio, et al. 2009. “Intergenerational Wealth Transmission and the Dynamics of Inequality in Small-Scale Societies.” Science 326 (5953): 682–88. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1178336.

O’Brien, Michael J, R Lee Lyman, Alex Mesoudi, and Todd L Vanpool. 2010. “Cultural and Linguistic Diversity: Evolutionary Approaches.” Source: Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 365 (1559): 3797–3806. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0012.

Pagel, Mark. 2012. Wired for Culture. London: Penguin Books.

Peter Turchin. 2016. Ultrasociety. Chaplin, Connecticut: Beresta Books.

Piketty, Thomas. 2013. Capital. Harvard: Belnap.

Pilling, David. 2018. The Growth Delusion. Great Britaij: Bloomsbury.

Potter, Wendell, and Nick Penniman. 2016. Nation on the Take. New York: Bloomsbury.

Richerson, Peter, Ryan Baldini, Adrian V. Bell, Kathryn Demps, Karl Frost, Vicken Hillis, Sarah Mathew, et al. 2016. “Cultural Group Selection Plays an Essential Role in Explaining Human Cooperation: A Sketch of the Evidence.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 39 (2016): e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1400106X.

Scheidel, Walter. 2017. The Great Leveller. Piceton: Princeton University Pres.

Scott, James C. 2017. Against the Grain A Deep History of the Earliest States. Yale University Books.

Service, Elman. 1971. Primitive Social Organisations: An Evolutionary Perspective. 2nd ed. New York: Random House.

Service, Elman R. 1975. Origins of the State and Civilisation: A Process of Cultural Evolution. New York: W.W. Norton and Co inc.

Shaxaon, Nicholas. 2012. Treasure Islands. London: Vintage.

Tajfel, Henri. 1974. “Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour.” Social Science Information 13 (2): 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204.

Tomasello, Michael, Alicia P Melis, Claudio Tennie, Emily Wyman, and Esther Herrmann. 2012. “Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation: The Interdependence Hypothesis.” Anthropology 53 (6): 673–92. https://doi.org/10.1086/668207.

Turchin, P., T. E. Currie, E. A. L. Turner, and S. Gavrilets. 2013. “War, Space, and the Evolution of Old World Complex Societies.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (41): 16384–89. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1308825110.

Tylor, E. B. 1974. Primitive Culture. New York: Gordon Press.